Badzine takes an in-depth look at the Korea Armed Forces Athletic Corps, a system that is crucial in maintaining the international sports competitiveness of a nation that has officially been at war for over sixty years.

Story and photos by Don Hearn

For the second time in four years, Korea has seen its top badminton players in two disciplines forced to take a temporary leave of absence from international competition to perform their military service. However, once again, the Korea Armed Forces Athletic Corps, known here as the Sangmu team, has served to minimize the impact on the careers of some of Korea’s finest athletes.

In early 2009, it was Jung Jae Sung who became the first world #1 badminton player to be forced to leave the national team for four weeks of basic training at the beginning of a 2-year stint as a member of the Sangmu team. He was accompanied, at the time by then top-ten singles player Park Sung Hwan.

This year, Yoo Yeon Seong and Son Wan Ho were Korea’s highest-ranking active players in mixed doubles and men’s singles respectively when they were called in to fulfill their military service.

The compulsory military service is a rite of passage for all young Korean men, thousands of whom get called up each year and must put university education or jobs on hold for 21 months, a period that has undergone substantial reduction over the decades. In the Republic of Korea, which is still officially at war with a neighbour that boasts one of the world’s largest standing armies, the system is taken very seriously. Many a political career has been severely damaged by allegations that a son has been exempted from conscription through a powerful parent’s influence.

There’s gold in them platoons!

Still, Koreans can tend to be much more understanding when it comes to their sporting heroes being forced to leave the limelight and this extends beyond merely the public to the military and political leadership. In fact, the Sangmu team system came into being when the nation was under a military dictatorship in the 1980s and national security had to accept a compromise for the sake of national pride.

“The Sangmu team system was instituted as part of an effort to improve the medal take in the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympics, both of which Seoul was hosting,” explains Sangmu Badminton Team Head Coach Yoon Joong Oh. “Up until that time, young athletes learned their sport in middle and high school but they all had to go to the army during their university years and that always meant a two-year interruption in their sporting careers.

“In order to prevent this interruption, the President called for this special type of military service to be set up which would allow the athletes to continue playing their sport at the same time they were putting in their two years.”

Coach Yoon was called on to head up the badminton division of this programme in early 1984 and he will hand over the reins to a successor this spring. His playing days as an elite athlete came in the 1970s, before the new system was set up and when he was called up, his own career was interrupted.

Yoon himself is not actually a soldier, though, even in his present job. He is classified as a public servant. In fact, there is no one in elite badminton in Korea who is also a career soldier.

The stars not taken

Yoon came up through the same high school as such luminaries as Park Joo Bong, Kim Dong Moon, and Ha Tae Kwun and the same university as Kim Moon Soo and Shon Seung Mo, but these are some of the famous names that do not appear on the alumni list of those he coached on the Sangmu team. This is because of an even bigger concession the government has made to Korea’s top athletes.

“President Chun Doo Hwan took particular care of the athletic community,” says Coach Yoon. “During his regime, winners at World Championships and at the Universiade were also exempt from military service but these days the exemptions are limited to Olympic medallists and Asian Games gold medallists.”

These exemptions affected most of two generations of badminton players, especially given the men’s team golds won at the Asian Games hosted by Korea, in 1986 and 2002. Since then, Lee Hyo Jung added two more names to the exempted list when she won mixed gold with Lee Yong Dae and Shin Baek Cheol, at the Olympics and Asian Games respectively.

“Park Sung Woo, who is currently coaching in Japan, was one of the earlier famous players who came through this system,” Yoon points out. “He reached as high as #2 in the world rankings and he was a Sangmu player in 1994-5.”

The free pass pressure

The prospect of getting a complete exemption from military service is obviously a welcome one for athletes, but as it is tied now to two events that are already some of the highest-pressure situations for badminton players, this can be as much a curse as a blessing.

“Last year at the London Olympics, Ko Sung Hyun and Yoo Yeon Seong looked, by their ranking, as if they might finish in the medals,” said Coach Yoon, “but they were under a lot of pressure because not winning one meant they were likely going to have to do their military service. In the end, they didn’t make it past the first round.

“In 2008, Jung Jae Sung was in the same position. After Beijing, he was quite frank about the amount of pressure he felt during the Olympics, since he was getting so close to the age limit and an Olympic medal was the only thing that was going to get him out of it.”

2012 Olympic bronze medallist Jung Jae Sung playing for Sangmu in Korea's Summer Championships in 2009 © Don Hearn for Badzine

But if a top player can play for the Sangmu team, not be confined to a base like a regular soldier, still train with the national team, and still compete internationally, why is the prospect of this type of conscription still so daunting?

“When the men are playing for a pro team, they draw a salary which is considerable, but as soldiers, they are entitled only to the income of a private,” explains Yoon. “There really isn’t any benefit to being on the Sangmu team. Nobody comes here by choice, only when the government requires it.

“The only benefits would be the fact that if not for the Sangmu team system, they’d be doing regular military service and wouldn’t be able to keep up their badminton training at all. Also, some find it is good for their mental strength,” Yoon admits, echoing what Yoo Yeon Seong found he had gained from his military experience so far (see related article here).

“But compared to those, you have the substantial financial hit plus the fact that the life itself has a whole lot less freedom than when they are at a pro team. They have to get up at 6 every morning and go through inspection and many of the same routines as any other soldiers.”

The other factor is that only four players each year are allowed to join the Sangmu team. They are selected based on a number of criteria, including their national team experience, competition results and also a fitness test.

“Any players who aren’t selected for the Sangmu team have to spend their two years as regular soldiers and they are thus unable to play their sport at all and it is very difficult for them to start back up again afterward.”

When the Sons go off to fight…

For a player like Son Wan Ho, who really only had an outside shot at a medal in London, the choices were simpler: “I knew as of September that I was going to have to do my military service this year so I didn’t feel a lot of pressure. I knew it was something I had to do.

“It’s quite a bit different for us because we know that once basic training is over, we’ll be at the Sangmu training centre. Guys who are in the regular army have a lot less freedom and the environment is totally different,” Son added.

However, getting his marching orders did mean a little more than a four-week interruption to Son, who was recovering from injury following the Olympic Games.

“It was actually difficult,” said Son. “As soon as I got to the base for basic training, I had to do exactly what I was told, along with the other guys. There was no chance to do anything else in terms of treating my injury or getting back to form so I think it delayed my return to form. Had I not had to start my military service, I think I could have gotten treatment and been match-ready sooner.

“I was in a lot of pain after the Olympics but at this point, I think my recovery is basically complete. If I get the call to return to the national team, I think I am ready to compete internationally.”

Stay with the programme?

In fact, badminton was on the chopping block a few years ago from the Sangmu programme. Korea will be hosting the Military World Games in 2015, an event that is very important to the armed forces athletic programme. However, as badminton is not part of those Games, it was in danger of being dropped altogether in an effort to focus on events that could net Korea more gold at home.

The plan to scale back was scrapped, however, at the badminton team will be moving in the next few months to the brand-new facility in Mungyeong, where the Military Games will be held, even if the players will not be active during the event itself.

The number of total soldiers in the Korean military is fixed to maintain a certain strength in comparison to North Korea’s army and so any changes in the head count in the sports programme affects the number in the regular forces and hence, such decisions are made at the very highest levels. In fact, some have even called, at certain times, for the abolition of the Sangmu operation.

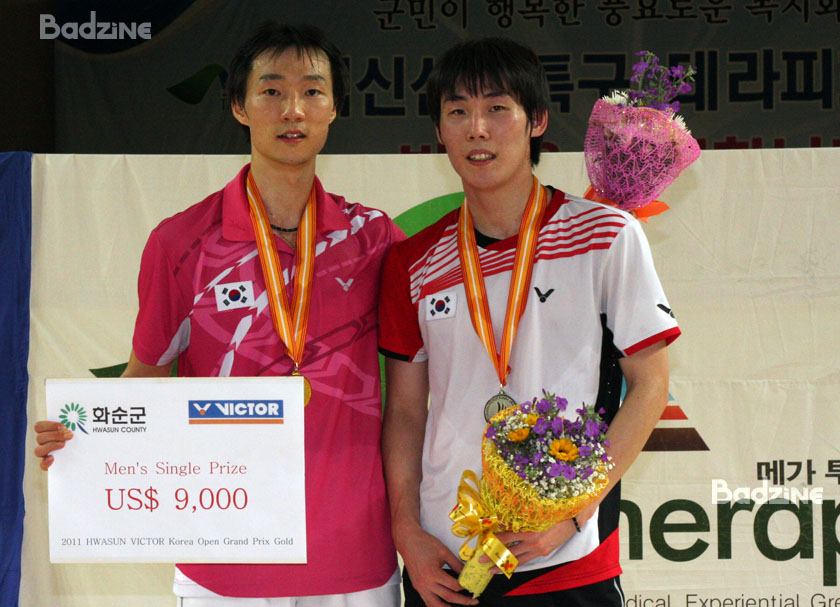

Son Wan Ho (right) finishing runner-up to Lee Hyun Il at the Korea Grand Prix Gold in 2011 © Don Hearn for Badzine

For now, though, the Sangmu system is in full force and it is providing elite athletes such as Yoo Yeon Seong and Son Wan Ho the opportunity to stay match fit and ready to answer their nation’s call as something other than soldiers. This is particularly good news for Korea in 2013 since these two national team players just happen to be specialists in the only two disciplines where the country does not have an entry in the world’s top ten.

“If I am asked to return to the national team, I’d really be focussed on the Incheon Asian Games,” says Son Wan Ho. “Since men’s singles is really in a low period right now, I’d really like to get the chance to get back and build it back up again.”

First, though, Son and Yoo are being asked to prove themselves as they lead the Sangmu team into Korea’s Spring Team Championships, which start today and will feature all of the top pro teams in the country. After they play for the army’s honour on the badminton courts of Korea, they may get their chance to play for Korea again around the world.

![National security, national pride: Korea’s Armed Forces Badminton Team Badzine takes an in-depth look at the Korea Armed Forces Athletic Corps, a system that is crucial in maintaining the international sports competitiveness of a nation that has officially been […]](http://www.badzine.net/wp-content/uploads/Newsflash-thumbnail.png)

Leave a Reply to Anonymous Cancel reply